Nonlinearity

This is an update to my Analysis Philosphy page, which is still working towards completion

Nonlinearity is a commonly-misunderstood problem when it comes to data analysis, mostly because our profession has once again managed to find a way to use a simple-sounding term in a way that’s counterintuitive to lay audiences. (See also Artificial Intelligence is Dumb.) When people think about nonlinear response variables, they think of functions that have non-linear relationships. And we tell them that one of the assumptions required for regression is linear relationships between your predictor and response variables. But of course we can include nonlinear terms in our linear regression models provided there’s a linear relationship between the response and the nonlinear function of the predictor and ….

Anyways, the challenge isn’t fitting a regression with a quadratic term but rather recognizing when that quadratic term is necessary.

Nonlinearity and Prediction

There are a couple of reasons we build models. If we want to understand an underlying mechanism, we try to choose terms that are interpretable and reflect an underlying mechanism. If we choose a nonlinear term, it’s because we think there’s plausibly a nonlinear relationship. But this isn’t why we build models a lot of the time. These days, especially when you start talking about machine learning and data science, we’re less interested in underlying relationships and more interested in minimizing prediction error.

In just about ever intro statistics class you take, you’re taught not to predict outside of your data. “Extrapolation”, you’re told, “is dangerous and can lead you astray.” The rationale here is that the relationship between your variable may change outside the range where you’ve collected data. However, if your response surface is sufficiently nonlinear, interpolation can be equally dangerous. This isn’t typically taught in stats classes because (1) most of your models assume nice, smooth relationships and (2) data are often relatively small samples (or at least nothing that could plausibly be called “big data”) and so over-fitting is less likely to occur.

In complex, real-world problems, you’ll occasionally run into severely nonlinear response surfaces. More accurately, these are discontinuous response surfaces, where specific variable threshold result in “steps”. Suppose a team is considering tinkering with their lineup, substituting a better defensive player for one of their good shooters. Now generally, the team’s net rating will increase linearly with an individual player’s 3pt%. But if that percentage drops below a certain threshold (basically the point at which it becomes beneficial for the defense to allow that player to shoot whenever possible), the team can double off that player with impunity, potentially mucking up the entire team. So the same marginal decrease in 3pt% could take the half-court offense from “pretty good” to “average” or from “average” to “worst in the league” depending on how good the player is. In cases like these, its important to allow for severe nonlinearity in your estimators, or you’ll produce some unexpectedly large prediction errors.

The other side of that coin is the type of data science which fits highly non-linear predictive models. All flavors of neural networks and deep learning fall into this category. Here, the models are highly nonlinear because the data is, too. Unfortunately, this can make these models highly unstable. This is why you get adversarial examples and the like: Wherever you are in your model space, there’s always a super-steep curve somewhere nearby. Basically, to make problems like image recognition tractable, you’ve got to massively over-fit your models to a jagged, weird space.

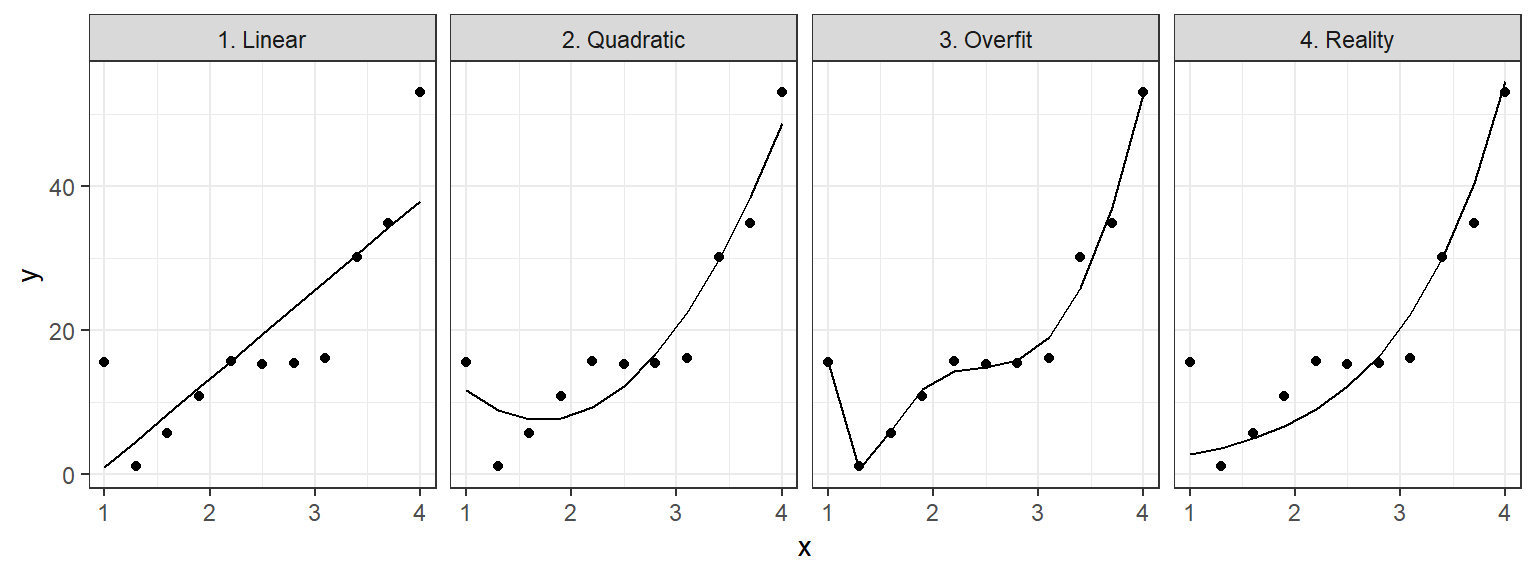

And over-fitting (“too much nonlinearity”) can be as dangerous as under-fitting (“non enough nonlinearity”). Consider the examples below:

These are pretty trivial, but I think they do a good job of illustrating the point. If we were to try to use either of the first two fits beyond the support of our data, we’d make pretty egregious errors. But if we try to use the 3rd fit, we’d also make egregious errors even within the range of the data we’ve collected.

Complexity is complex

There’s no one-sized fits-all approach to dealing with this. The truth of the matter is that errors are inevitable when dealing with complex problems. The only thing to do is choose a strategy to minimize their frequency and magnitude. So I always try to think about whether it’s worse to build a model that’s too complex or too naive for a particular application. That way at least I’ll have a direction in which to iterate.